The Keepers

from the Record, Fall 2023

by Alexandra Evans

Set in what Caroline Emmons, director of the Center for Public History, calls a “laboratory of history,” Hampden-Sydney has always drawn historophiles. Emmons credits this to a number of factors, including the position of the College—both geographically and temporally in our nation’s history— and the strength of the Hampden-Sydney History Department.

“Over the past 10 years, Hampden-Sydney College has graduated more history majors as a share of students than any other college or university in the nation. According to The American Historical Association, approximately 1.2 percent of undergraduates nationally majored in history between 2012 and 2022. Hampden-Sydney’s average across those ten years is 13.6 percent,” reports Elliott Associate Professor of History James Frusetta.

With a steady stream of students eager to learn about history and the ever-growing need for transparency in historical interpretation, the establishment of the Center for Public History in 2019 was a natural progression for the history department. The Center focuses on oral history, historic preservation, museum studies, archaeology, and archives and digitization, essentially merging the academic study of history with practical ways that H-SC graduates can apply their degrees after they leave the Hill.

“We are very well positioned to explore the continuing relevance of history and the challenges in interpreting history for a diverse public,” Emmons says. “Teaching students about the production and interpretation of history for a public audience is a perfect complement to the Rhetoric program and to Compass, the College’s experiential learning program. In other words, all the pieces were already here and it’s been exciting putting them together into a program.”

Read on to discover how eight Hampden-Sydney history majors across five decades have dedicated their professional lives to the preservation, interpretation, and conservation of American history.

While volunteering as a docent at Jamestown Settlement in high school, Nathan Ryalls ’11 discovered that he really enjoyed making history exciting and relevant to the general public. Ryalls was encouraged by Jamestown curator Daniel Hawks ’61 to consider Hampden-Sydney despite there being no formal public history or museum studies program at the time. Emmons actually credits Ryalls with the idea for establishing the Center for Public History.

While volunteering as a docent at Jamestown Settlement in high school, Nathan Ryalls ’11 discovered that he really enjoyed making history exciting and relevant to the general public. Ryalls was encouraged by Jamestown curator Daniel Hawks ’61 to consider Hampden-Sydney despite there being no formal public history or museum studies program at the time. Emmons actually credits Ryalls with the idea for establishing the Center for Public History.

“Nathan rightly pointed out that H-SC is well situated for the study of history given its physical and intellectual location at the crossroads of many important moments in American history, from the nation’s founding to the Civil War to the civil rights movement,” Emmons says.

At Hawks’ suggestion, Ryalls began working with Director-Curator of the Atkinson Museum Angie Way from the moment he stepped on campus and continued all four years, going on to serve on the board of the Museum after graduating.

After completing his master’s degree in history at James Madison University, Ryalls has made a career out of just what called him to public history in the first place: making history exciting to the public. As guest experience and design manager at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Ryalls works to streamline the guest experience at Colonial Williamsburg, liaising with various guest-facing departments such as the tradespeople, museum theater actors, and nation builder characters to create programming and schedules that create a cohesive narrative experience for the guests.

Once bringing in over a million visitors a year, Colonial Williamsburg has experienced a drastic drop in guests coming through the park, which Ryalls laments. Though, he relishes the challenge of keeping a premier destination. To do this, Ryalls and his team are taking age old topics like democracy, freedom, revolution, ingenuity, and community and inviting visitors to create links between the circumstances surrounding these topics in 18th century Colonial America and their places in today’s world. “Interpretation is, at its core, provocation. We want our guests to find relevant ties to their own lives and then to be active participants in their community,” Ryalls explains. “That goes beyond just voting; it’s being active in the PTA and your church and the farmers’ market. Trying to improve community life.”

“History is not done and dusted,” Ryalls says. “It’s an evolving field with new questions and new stories emerging and new ways we can learn from the past.”

Echoing Ryalls’ sentiments, Dr. Carter Hudgins ’00, president and CEO of Drayton Hall Preservation Trust in Charleston, South Carolina, says: “The beauty and the challenge of what we do is that you come to the table with two questions, but the answers to those two questions lead to four more questions. It’s all part of an evolution.”

Echoing Ryalls’ sentiments, Dr. Carter Hudgins ’00, president and CEO of Drayton Hall Preservation Trust in Charleston, South Carolina, says: “The beauty and the challenge of what we do is that you come to the table with two questions, but the answers to those two questions lead to four more questions. It’s all part of an evolution.”

Holding both master’s and doctorate degrees in history and material culture from the University of London, Hudgins expands on some of the new questions his team is trying to answer about life at Drayton Hall—an 18thcentury plantation in the South Carolina low country—a property that he started working at in high school, when he was a member of the grounds crew. “Archaeology at Drayton Hall has been reactive up to the present— meaning that we would only conduct an excavation ahead of any projects that could disrupt the archaeological record,” he explains. “But we now have a fully funded archaeology department, and we’re able to create aresearch strategy and set about finding answers. One of our priorities is to find the community where the enslaved people lived both in the main house and out across the landscape. We want to be as accurate and authentic as possible. Archaeology holds you to that because what you find is what happened.”

“There’s so much to learn from old properties like Drayton Hall,” Hudgins says. “For instance, Drayton Hall is the first fully executed example of Palladian architecture in the U.S. It is ground zero in the U.S. for classical design, and people are still coming to the site and examining what was built in the 1740s and why.”

“You can think of these properties almost like a grandparent.” Hudgins continues. “They’re living and breathing, maybe retired and slower, but the impact they have on us today is extremely powerful. They can provide wisdom and warning as to what was good and bad respectively, teach us what to do and what not to do, and help us move forward.

“We need to understand where the nation came from and what impact that has on the country today,” agrees Clayton James ’91. “Doing so can govern how we react today and what we should and should not do. It’s important to honestly represent the past and fairly tell the whole story.” James, who is managing director of Jamestowne Investments, volunteered as president of The Rosewell Foundation in Gloucester, Virginia, from 2017 until the summer of 2023 when The Rosewell Foundation merged with The Fairfield Foundation. James is still actively involved in the management of Rosewell and currently consults for The Fairfield Foundation.

“We need to understand where the nation came from and what impact that has on the country today,” agrees Clayton James ’91. “Doing so can govern how we react today and what we should and should not do. It’s important to honestly represent the past and fairly tell the whole story.” James, who is managing director of Jamestowne Investments, volunteered as president of The Rosewell Foundation in Gloucester, Virginia, from 2017 until the summer of 2023 when The Rosewell Foundation merged with The Fairfield Foundation. James is still actively involved in the management of Rosewell and currently consults for The Fairfield Foundation.

Once the nucleus of the colonial economy, Rosewell was built in 1725 by the affluent Page family. James points out, though, that Rosewell’s legacy does not begin or end with the Page family. Built on Pamunkey native land at the location of Pocahontas’ alleged birthplace and constructed and run by enslaved Africans, Rosewell is a pinpoint on the timeline of Virginia and American history.

“Without the contributions of the enslaved Africans, Rosewell wouldn’t have existed,” James explains. And without Rosewell, the future of the budding nation might have looked very different. Despite the shame surrounding the history of enslavement at Rosewell, the Foundation has made it a point not to shy away from that aspect of the home’s history. James notes that it does no one a fair service to shy away from that dark corner of the home’s history. “By using it to educate the public, we hope to bring long overdue recognition and perhaps a sense of pride to the descendants of that community,” he says.

That is a sentiment that Jeffrey Harris ’90 can appreciate. Holding a master’s degree in history from Clemson University, Harris spent six years at the National Trust for Historic Preservation as director of diversity before becoming an independent historian and historic preservation consultant. Harris also served on the Virginia Board of Historic Resources—including as vice chair for a time—from 2019 until January 2023. Harris has expertise in diversity issues in historic preservation and historic interpretations; and audience and board development with historic sites, non-profit organizations, and academic institutions. In an article written for the National Park Service (NPS) titled “Where We Could Be Ourselves”: African American LGBTQ Historic Places and Why They Matter, he recalls a trip to Montpelier—the home of James and Dolley Madison—and a docent who spoke of the praise that the Madisons received for the beauty of their home and grounds:

That is a sentiment that Jeffrey Harris ’90 can appreciate. Holding a master’s degree in history from Clemson University, Harris spent six years at the National Trust for Historic Preservation as director of diversity before becoming an independent historian and historic preservation consultant. Harris also served on the Virginia Board of Historic Resources—including as vice chair for a time—from 2019 until January 2023. Harris has expertise in diversity issues in historic preservation and historic interpretations; and audience and board development with historic sites, non-profit organizations, and academic institutions. In an article written for the National Park Service (NPS) titled “Where We Could Be Ourselves”: African American LGBTQ Historic Places and Why They Matter, he recalls a trip to Montpelier—the home of James and Dolley Madison—and a docent who spoke of the praise that the Madisons received for the beauty of their home and grounds:

“I understood that the praise…needed to be directed toward those who actually did the work to make Montpelier beautiful. I began to swell with pride at THEIR work…I realized, for myself, that there was no need to feel shame over slavery, something that many people do feel (along with anger and sadness). Instead, I offered congratulations, silently, to those spirits who did that work, and did it well. If no one in their lives offered genuine thanks for THEIR work, I wanted to do it those many years later, and I did.”

Harris says that the epiphany he had while contemplating the manicured grounds and well-preserved home could only have happened while standing in the place itself. “There’s something powerful about being able to look squarely at one’s past exactly where it happened, see it for what it was, and then learn from it,” he expounds.

Harris finds significance in engaging history through place, saying that it is one thing to read about history in a book but another thing entirely to experience the physical location where something important happened. In the NPS article, Harris goes on to talk about the sense of pride he felt when he moved into the Logan Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C., and visited the former homes of prominent African American LGBTQ residents:

“I recognized the deep need for the African American LGBTQ community not only to know where our predecessors made their history, but also to identify places that are still available for us to visit, even if that visit constitutes standing outside of a door, or driving by a building where something incredible happened.”

Harris explains that all too often historic places associated with LGBTQ individuals are located in areas slated for revitalization and in danger of being torn down or altered significantly. The places that are most likely to remain are those with previously unknown LGBTQ ties.

Knowing how quickly places of significance can be destroyed and the associated history lost to the public and the communities to whom it was important, Harris often wonders if important contemporary historic figures think about their legacy from a preservation perspective. “I want to know if there’s a place important to those people’s history that should be preserved for future generations to learn from,” he says. “Where would their National Register of Historic Places plaque be hung?”

Brian Grogan ’73 has also dedicated much of his professional career to preserving places of significance, but his medium is photography. A history major who developed his first roll of film in a dark room on the top floor of Winston Hall, now Brinkley Hall, 21-year-old Grogan never imagined his two interests would dovetail so uniquely.

Brian Grogan ’73 has also dedicated much of his professional career to preserving places of significance, but his medium is photography. A history major who developed his first roll of film in a dark room on the top floor of Winston Hall, now Brinkley Hall, 21-year-old Grogan never imagined his two interests would dovetail so uniquely.

For more than 30 years, Grogan has produced photographic documentation of the built history of the United States, with more than 10,000 photographs in the Library of Congress collections of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), and Historic American Landscape Survey (HALS)—the NPS’s Heritage Documentation Programs.

This fall Grogan has returned to campus as lecturer in the Fine Arts Department to teach a class titled Recording Historic Structures. The course will introduce Hampden- Sydney students to the history, legacy, and process of historic documentation in the United States, including hands-on field work such as researching and documenting historic structures on campus. He will also be photographing the college architecture and landscape to update an extensive study he did of the College in the mid-1990s. A collection of 45 fine art photographic prints from that earlier study are archived in Bortz Library Special Collections. A selection of those prints are now on display in Pannill Commons.

In addition to his preservation photography work, Grogan has also been deeply engaged for 25 years as a historian and documentary film maker in the Civil Rights era public school crisis in Prince Edward County. He has served as a citizen member and consultant to sub-committees of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission of the Virginia General Assembly; researched and edited an anthology of historical writings titled A Little Child Shall Lead Them: A Documentary Account of the Struggle for School Desegregation in Prince Edward County, Virginia; and done extensive research and production work on the documentary film They Closed Our Schools for which he is now raising completion funding.

Echoing Harris’s sentiments, Grogan says, “My appreciation of history is to get out of the history book or the classroom and stand where something of significance happened, not even necessarily something of great historical importance, but all things that contribute to the built history of the U.S. like one-room schoolhouses.” His photographs are a piece of the documentation that the NPS includes for each of the historic locations they document and archive in the Library of Congress. Other materials include architectural drawings and a written history of the building, structure, or landmark.

Grogan is contemplative as he relays what it’s like to stand in the middle of history in the making. “Oftentimes I’m taking the last photograph of a place that will ever be taken as the building or site is scheduled for demolition,” Grogan says. “Walking through an abandoned building or site—it’s like walking with ghosts.”

And while it might be tempting to romanticize these abandoned buildings, Grogan remains focused on the task at hand. “The difference between architectural and commercial photography is that commercial photography is designed to make a place look great,” he explains. “I walk into a place and photograph it just as it is, warts and all.”

Ed Ayres ’66 is also committed to presenting history warts and all. “Understanding how complex and twisted history can be is something I would like every American to understand,” he says. After completing a master’s degree at the University of Virginia, Ayres began his career as a historian in the 1970s working with archaeologists at the College of William and Mary. In 1988, he joined the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation as a public historian and was part of the team that created a new museum on the American Revolution at Yorktown.

Ed Ayres ’66 is also committed to presenting history warts and all. “Understanding how complex and twisted history can be is something I would like every American to understand,” he says. After completing a master’s degree at the University of Virginia, Ayres began his career as a historian in the 1970s working with archaeologists at the College of William and Mary. In 1988, he joined the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation as a public historian and was part of the team that created a new museum on the American Revolution at Yorktown.

Ayres’ foray into history was unexpected but nonetheless fulfilling. A patriotic man, Ayres came to Hampden- Sydney during the height of the Cold War with the goal of becoming a scientist and doing his part to protect the country and defeat communism. That is, until organic chemistry got in his way. After changing his major to history though, Ayres discovered another way to live out his patriotism: presenting the full and complete history ofthe nation he loves to its citizens, despite the ugly truths that history may reveal.

This path has, at times, forced Ayres to confront some of his own long-held beliefs, like when he “devoured” the Pentagon Papers and his eyes were opened to the complexity of history and politics.

“As a historian there are so many events that even I didn’t know happened until more recently, like the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921,” Ayres admits. As he strives to broaden his knowledge of American history outside of his professional expertise in the colonial era, Ayres hopes to achieve a realistic understanding of where the nation is in achieving the American dream of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all its citizens.

Ayres explains that in order to make an informed opinion, it is important for each American citizen to learn as much as possible about our nation’s history. It is a task he believes every generation should and does undertake in its own way, leading to new understanding about America’s collective history and that history’s place in the modern world. “Every generation understands the past from their own perspective,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that their understanding is any better or worse, but it’s different. Every generation revises its understanding of the past from a modern viewpoint.”

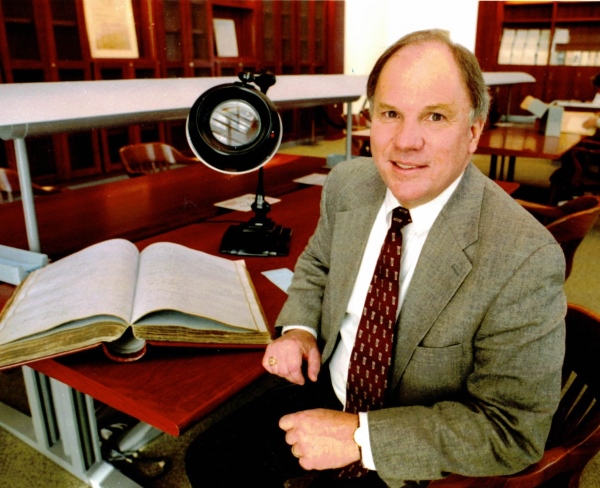

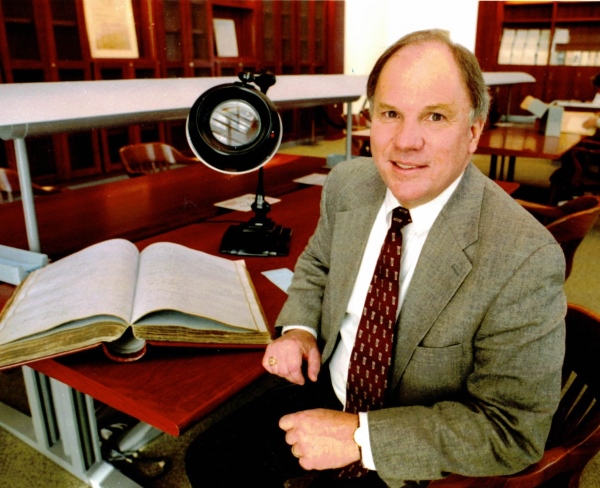

Retired Virginia State Archivist Conley Edwards ’67 also points to the Pentagon Papers as a reminder of the need for transparency in governance, a philosophy he holds dear as an archivist. “When the Pentagon Papers came out, it affected people’s trust and confidence in government,” he explains. “One of the things that archivists strive for is to provide unedited materials so that average citizens can come in and investigate an issue or an incident and form their own opinions.”

Retired Virginia State Archivist Conley Edwards ’67 also points to the Pentagon Papers as a reminder of the need for transparency in governance, a philosophy he holds dear as an archivist. “When the Pentagon Papers came out, it affected people’s trust and confidence in government,” he explains. “One of the things that archivists strive for is to provide unedited materials so that average citizens can come in and investigate an issue or an incident and form their own opinions.”

Edwards was first introduced to archival work during graduate school at the University of Richmond, where he obtained his master of arts degree in American history after serving in the Army. He led a Herculean effort over the course of his 35-year career at the Library of Virginia growing the state archives from 47,500 items in 1974 to 109,221,000 upon Edwards retirement in 2009. Edwards says that the Library of Virginia’s staff has led the way in state archiving across the nation, and the state’s archive is among the most visited in the nation. “The importance of having an extensive collection is that the public has a right to access those materials to see if their money is being well-spent,” Edwards explains.

“The government is doing the people’s business and the people have a right to know how those decisions are being made and how that business is being done.”

Although archives are often associated with major historical treasures or high-level government documents such as the Pentagon Papers, Edwards argues that the everyday documents often end up being the most illuminating historical materials.

“There was a period of historiography where the story was really of Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe— prominent figures like that,” Edwards says. “But in the late 20th century, the focus shifted to more personal stories of individual citizens at a local level. There’s no richer source of information than documents such as court proceedings or land deeds or tax records that depict life at a local level.”

Their paths and professions vary, but these alumni’s motivations are comparable and commendable: to both preserve and enhance the history of the nation they love, while recognizing the imperfections in that history and using those imperfections to educate their fellow citizens. Jeffrey Harris reminds us that “history is not good or bad, it just is.” Each of these historians possess a tenacity for the truth, pursuing their work as the Founding Fathers did: always challenging the status quo and continuously striving towards the goal of building a more perfect union.

More News Stories

While volunteering as a docent at Jamestown Settlement in high school, Nathan Ryalls ’11 discovered that he really enjoyed making history exciting and relevant to the general public. Ryalls was encouraged by Jamestown curator Daniel Hawks ’61 to consider Hampden-Sydney despite there being no formal public history or museum studies program at the time. Emmons actually credits Ryalls with the idea for establishing the Center for Public History.

While volunteering as a docent at Jamestown Settlement in high school, Nathan Ryalls ’11 discovered that he really enjoyed making history exciting and relevant to the general public. Ryalls was encouraged by Jamestown curator Daniel Hawks ’61 to consider Hampden-Sydney despite there being no formal public history or museum studies program at the time. Emmons actually credits Ryalls with the idea for establishing the Center for Public History. Echoing Ryalls’ sentiments, Dr. Carter Hudgins ’00, president and CEO of Drayton Hall Preservation Trust in Charleston, South Carolina, says: “The beauty and the challenge of what we do is that you come to the table with two questions, but the answers to those two questions lead to four more questions. It’s all part of an evolution.”

Echoing Ryalls’ sentiments, Dr. Carter Hudgins ’00, president and CEO of Drayton Hall Preservation Trust in Charleston, South Carolina, says: “The beauty and the challenge of what we do is that you come to the table with two questions, but the answers to those two questions lead to four more questions. It’s all part of an evolution.” “We need to understand where the nation came from and what impact that has on the country today,” agrees Clayton James ’91. “Doing so can govern how we react today and what we should and should not do. It’s important to honestly represent the past and fairly tell the whole story.” James, who is managing director of Jamestowne Investments, volunteered as president of The Rosewell Foundation in Gloucester, Virginia, from 2017 until the summer of 2023 when The Rosewell Foundation merged with The Fairfield Foundation. James is still actively involved in the management of Rosewell and currently consults for The Fairfield Foundation.

“We need to understand where the nation came from and what impact that has on the country today,” agrees Clayton James ’91. “Doing so can govern how we react today and what we should and should not do. It’s important to honestly represent the past and fairly tell the whole story.” James, who is managing director of Jamestowne Investments, volunteered as president of The Rosewell Foundation in Gloucester, Virginia, from 2017 until the summer of 2023 when The Rosewell Foundation merged with The Fairfield Foundation. James is still actively involved in the management of Rosewell and currently consults for The Fairfield Foundation. That is a sentiment that Jeffrey Harris ’90 can appreciate. Holding a master’s degree in history from Clemson University, Harris spent six years at the National Trust for Historic Preservation as director of diversity before becoming an independent historian and historic preservation consultant. Harris also served on the Virginia Board of Historic Resources—including as vice chair for a time—from 2019 until January 2023. Harris has expertise in diversity issues in historic preservation and historic interpretations; and audience and board development with historic sites, non-profit organizations, and academic institutions. In an article written for the National Park Service (NPS) titled “Where We Could Be Ourselves”: African American LGBTQ Historic Places and Why They Matter, he recalls a trip to Montpelier—the home of James and Dolley Madison—and a docent who spoke of the praise that the Madisons received for the beauty of their home and grounds:

That is a sentiment that Jeffrey Harris ’90 can appreciate. Holding a master’s degree in history from Clemson University, Harris spent six years at the National Trust for Historic Preservation as director of diversity before becoming an independent historian and historic preservation consultant. Harris also served on the Virginia Board of Historic Resources—including as vice chair for a time—from 2019 until January 2023. Harris has expertise in diversity issues in historic preservation and historic interpretations; and audience and board development with historic sites, non-profit organizations, and academic institutions. In an article written for the National Park Service (NPS) titled “Where We Could Be Ourselves”: African American LGBTQ Historic Places and Why They Matter, he recalls a trip to Montpelier—the home of James and Dolley Madison—and a docent who spoke of the praise that the Madisons received for the beauty of their home and grounds: Brian Grogan ’73 has also dedicated much of his professional career to preserving places of significance, but his medium is photography. A history major who developed his first roll of film in a dark room on the top floor of Winston Hall, now Brinkley Hall, 21-year-old Grogan never imagined his two interests would dovetail so uniquely.

Brian Grogan ’73 has also dedicated much of his professional career to preserving places of significance, but his medium is photography. A history major who developed his first roll of film in a dark room on the top floor of Winston Hall, now Brinkley Hall, 21-year-old Grogan never imagined his two interests would dovetail so uniquely. Ed Ayres ’66 is also committed to presenting history warts and all. “Understanding how complex and twisted history can be is something I would like every American to understand,” he says. After completing a master’s degree at the University of Virginia, Ayres began his career as a historian in the 1970s working with archaeologists at the College of William and Mary. In 1988, he joined the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation as a public historian and was part of the team that created a new museum on the American Revolution at Yorktown.

Ed Ayres ’66 is also committed to presenting history warts and all. “Understanding how complex and twisted history can be is something I would like every American to understand,” he says. After completing a master’s degree at the University of Virginia, Ayres began his career as a historian in the 1970s working with archaeologists at the College of William and Mary. In 1988, he joined the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation as a public historian and was part of the team that created a new museum on the American Revolution at Yorktown. Retired Virginia State Archivist Conley Edwards ’67 also points to the Pentagon Papers as a reminder of the need for transparency in governance, a philosophy he holds dear as an archivist. “When the Pentagon Papers came out, it affected people’s trust and confidence in government,” he explains. “One of the things that archivists strive for is to provide unedited materials so that average citizens can come in and investigate an issue or an incident and form their own opinions.”

Retired Virginia State Archivist Conley Edwards ’67 also points to the Pentagon Papers as a reminder of the need for transparency in governance, a philosophy he holds dear as an archivist. “When the Pentagon Papers came out, it affected people’s trust and confidence in government,” he explains. “One of the things that archivists strive for is to provide unedited materials so that average citizens can come in and investigate an issue or an incident and form their own opinions.”