Born a Change Maker

from the Record, Spring 2021

By Alexandra Evans

Diversity and diversification are two guiding principles by which Warren Thompson ’81 has lived his life, and they have served him well. Founder and president of award-winning Reston-based Thompson Hospitality—the largest minority-owned food service company in the country and named 2010 Company of the Year by Black Enterprise and 2017 Number One Minority Owned Company by Washington Business Journal—Thompson has become an agent for change in the food service industry and in the communities that he loves through a commitment to innovation and inclusion.

The Early Days

Born into a tight-knit family in rural Windsor, Virginia, Thompson is the son of entrepreneurs and educators. His father, Fred Sr., was a math teacher and principal, and his mother, Ruby, taught home economics. “Until I was in middle school, my family rode to and from school together every day,” Thompson says. “And every day after the final bell rang, I would either go to my father’s classroom and learn high school algebra, or I would go to my mother’s classroom and learn how to cook.” It is no surprise that Thompson has made a successful career in the food service industry. Hospitality and business are simply in his blood.

In a still-segregated southern Virginia, Mr. and Mrs. Thompson were employed by the all-Black Georgie Tyler School and earned about 60 percent of what white teachers at the neighboring school made. So to make ends meet, the Thompson family ran a variety of businesses together including raising and harvesting hogs and buying and selling produce.

Despite their busy schedules, the Thompson family made spending quality time together a priority. Every Friday, the family of five traveled to Portsmouth to get groceries and have dinner at Shoney’s. It was during one of these family outings when he was 12 that Thompson got his first glimpse into his future.

“Growing up in that part of Virginia in an African-American community, my only real exposure to business was going to a restaurant,” Thompson explains. “Most people in my neighborhood worked at either the meat packing plant or the shipyards in Newport News. But sitting in that Shoney’s and watching people come in with friends and family and have their meals, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s a neat way to make a living.’”

When he expressed his interest to his mother, she told him that he could do anything he wanted to as long as he worked hard. The entrepreneurial young man took that advice to heart. As he got older, Thompson started playing an integral part in the family enterprises, even buying his father out of their hog business when he was just 16 years old. That same year, Thompson bought an older model blue school bus with a brand-new engine at auction so he could more easily transport peaches and apples from the mountains of Virginia to the tidewater region; he then sold the produce to local grocers and roadside stands. And with all of his spare time, he ran a lawn mowing business, servicing 12 to 15 lawns a week.

A Hill to Climb

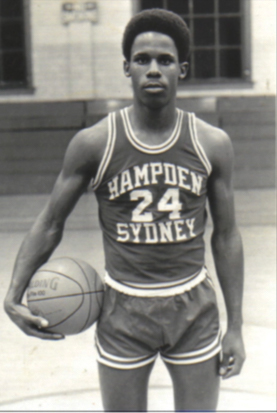

Working toward his goal of going into the restaurant business, Thompson followed his brother, Fred Thompson, Jr. ’79, to Hampden-Sydney.

“I had never heard of Hampden-Sydney. But Fred was friends with brothers Dick Holland ’74 and Greg Holland ’77, and they encouraged him to apply. I came to visit Fred when he was a freshman, and I just fell in love with the College,” Thompson says. “H-SC isn’t far from my hometown, and with my family being so close, it really worked for me to follow my brother there.”

As one of only about a dozen Black students at the time, Thompson encountered resistance to his presence on the Hill. He recalls experiences both in his classes and during social activities that illustrate the obstacles and trauma people of color often face. Thompson became determined not just to make it to commencement but to make an impact during his time at Hampden-Sydney.

Thompson and the other Black students on campus banded together to ensure that their voices were heard in all corners of College life. They earned positions in student government and on the Student Court, wrote for the newspaper, and created the Minority Student Union (MSU). Their advocacy extended beyond the College gates, as Thompson and the MSU used their College-sponsored funding to support Farmville-area literacy programs to empower the local Black community that had been negatively affected by the school closings of 1959 to 1964. Thompson himself was elected student body secretary/ treasurer, served on the Student Honor Court, and played basketball while at Hampden-Sydney. He also ran for student body president but lost by just 12 votes in the third run-off election.

The Power of Perseverance

“One thing that really attracted me to Hampden-Sydney was its graduate school matriculation rate, which was about 40 percent at the time. And I knew I wanted to get an MBA before I started a career,” Thompson says.

During his junior year at H-SC, Thompson attended a presentation by a representative from the University of Virginia’s (UVA) Darden School of Business and felt that he had found the MBA program for him. There was a catch, though. Darden did not accept students right out of undergrad, instead requiring at least two years of work experience to be accepted into their MBA program.

But Thompson didn’t want to wait. After all, he had three successful business ventures and close to 10 years of work experience under his belt. “So I made my pitch,” Thompson says. “And I was told no a couple of times. But I kept making my pitch as to why I should be allowed to go directly from undergrad. And finally they agreed.”

Aside from the MBA program being the top program in the Commonwealth at the time, Thompson had a personal motivation to pursue a UVA education. His father, Fred Sr., had been denied acceptance to the university because he was Black. But by 1992, all three Thompson children held degrees from UVA.

Between his first and second year at Darden, Thompson earned an internship with Marriott, a fast track program that accepted 10 to 12 MBAs from top institutions such as Harvard, the Wharton School, and Darden. At the end of the program, one intern would be offered a full-time, postgraduation position reporting directly to Richard Marriott. Thompson’s innovative upgrade to a food distribution system was implemented company-wide, improving product quality, saving countless hours in labor, and earning him that coveted post-graduation position.

So after graduating from Darden in 1983, Thompson entered the corporate world as a full-fledged MBA, and was on his way to fame and fortune—flipping burgers at Roy Rogers. Yes, you read that right. Richard Marriott started all of his MBA employees off at the bottom of the food chain, instilling practical knowledge of every aspect of restaurant operations. Thompson took on the challenge with grace, noting that, of course, his MBA classmates came by to order a meal.

“It wasn’t very long before they were coming by to ask me for a job,” Thompson laughs.

On his first day at Marriott, Thompson shares, a senior vice president called him into his office and told him, “Your career is going to be different than Chuck and Steve just because of the color of your skin. As a Black person, you’re not going to have the same opportunities.”

“And he was right,” Thompson says. “It was difficult breaking certain color barriers, but my experiences dealing with racism at Hampden-Sydney and Darden had prepared me well to deal with that.”

Building a Legacy

When he started at Marriott, Thompson envisioned spending seven years with the company, leaving to start his own business by the time he was 30.

“My great-great-grandfather Cleave was a slave on a plantation just outside of Charlottesville,” Thompson explains. “He learned the blacksmith trade, and when he was freed at the age of 30, he started his own blacksmith business. And I always used that as a kind of guide for my life. When I was 30, I wanted to be free of the proverbial plantation and to start my own business at that time.”

Thompson ended up staying with Marriott for nine years, putting him in the right place at the right time when the company decided to sell off its restaurant properties to focus solely on the hotel business. In 1992 Thompson approached the CEO with a proposition to buy the Big Boy restaurants in the D.C. market. Collaborating with the leaders of both Shoney’s and Marriott, Thompson orchestrated a leveraged buyout of 31 Big Boy restaurants with $100,000 of his own capital and backing from Marriott. And so Thompson Hospitality was born.

As Shoney’s restaurants averaged $300,000 more in annual revenue than Big Boy, Thompson converted 27 of the 31 Big Boy locations to Shoney’s at a pace of one restaurant per month. The first restaurant conversion was up 40 percent in the first few months, and Thompson and his team started celebrating, believing they had struck gold. But six months down the road, that first restaurant’s numbers were flat compared with the prior year.

Feedback revealed that customers were excited at first, but then decided that despite the cosmetic upgrades, Big Boy and Shoney’s were not really that different, and their issues remained. So, after 10 months in business, Thompson knew he had to make some hard decisions fast.

Having planned to get into contract food service in year five, following the Marriott model, Thompson decided to speed up the timeline.

“One night I had a dream that my father told me to go after a contract with St. Paul’s College, his alma mater,” Thompson says. “So I called the college and managed to speak to the president, who actually went to school with my father. And within 10 days we had the contract.” This quick thinking and calculated risk-taking saved Thompson Hospitality.

Today, Thompson Hospitality is the largest Historically Black College and University (HBCU) food service provider in the country. But as Thompson learned in that first 10 months, diversification is key to survival. This means that Thompson Hospitality is not just a food service company, it is a full-service hospitality provider. The company provides healthcare, janitorial, landscaping, and plant operation services in addition to running an array of successful restaurant endeavors, and they recently entered the hotel industry. Their diverse portfolio has enabled Thompson Hospitality to weather the COVID-19 pandemic so far, with some sectors growing year-over-year in 2020.

Having seen the trends of the industry swaying toward fast casual nearly 10 years ago, Thompson has adjusted his approach to the restaurant segment of his business. He credits the organization’s steadfastness throughout 2020 to having the right mix of full-service and fast casual locations. He continues to innovate as he sees new trends or needs emerging and has begun building out ghost kitchens in several of his eateries, with one brand being street-facing and up to four other brands operating as delivery-only. This approach enables one location to house four or five operations, maximizing profits and drastically cutting operational and real estate expenditures.

Some of Thompson’s approach is informed by the various boards that he sits on.

“I like to get on public boards where I think I can learn something,” he says. “I spent 12 years on the board of Federal Realty, which is one of the top retail real estate companies in the country. I got a chance to look at what the most successful restaurants were doing from a real estate or landlord’s perspective.”

Paying It Forward

As one of the newest members of the Hampden-Sydney Board of Trustees, Thompson is excited to be involved in the progress of his alma mater.

“My passion for diversity and inclusion is very much aligned with where the school is headed,” Thompson says. “The College has done a tremendous job of creating a much better environment for minority students.” Just as he believes diversification is the key to business, so too is diversity necessary for the success of the College’s mission “to form good men and good citizens.”

“Diversity is as much a benefit to the majority student as it is to the minority,” Thompson says. “It helps us to create a better, more informed citizen. We’re trying to create a graduate who can do well in corporate America or as a business owner or wherever, and we can’t do that without exposing him to diverse perspectives and experiences.”

The Thompson Scholarship at Hampden-Sydney is awarded to students who have demonstrated a commitment to diversity and inclusion. Thompson hopes to encourage the next generation of students to continue disrupting the status quo, because as he states, “Once you get that in your blood, and you want to be a change-maker, you never stop.”